By T. Perry Bowers

As you develop skills as a recording engineer, you get an intuition about things. You start to use your ears more than your intelligence. The people who work for me have all been through technical school. It’s a requirement to work here. They are Pro Tools certified and trained in all the (mostly unnecessary) technical details of recording.

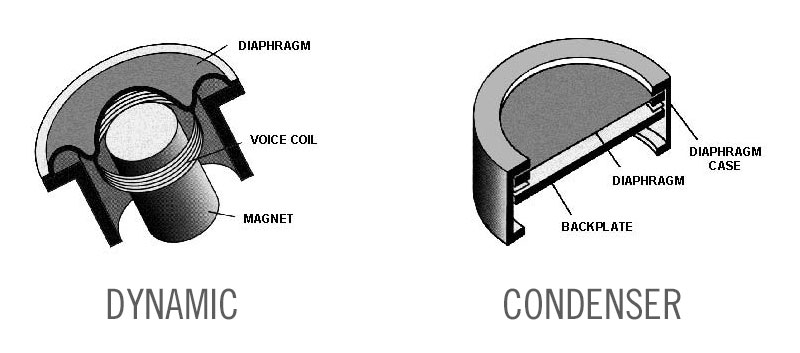

But I’m not going to get too technical here, partly because I don’t understand all the technical aspects of these kinds of microphones, but also partly because it doesn’t really matter. Let’s just talk as laymen about the two most common styles of microphones.

The Dynamic Microphone

The Dynamic Microphone

This is the microphone you use when you’re singing live. The diaphragm* on a dynamic microphone is stiff so even when you put a lot of pressure on it, it doesn’t distort. Think of it as a tight spring that moves ever so slightly with the pressure of your voice. When you sing through a dynamic microphone in a live setting, you can use proximity to your advantage. The way proximity works on a dynamic microphone does take some skill to master though. Depending on the microphone, the difference between loud and barely audible may only be a matter of half an inch.

Has your live engineer ever told you to “eat the mic”? What he wants you to do is give him a solid signal all the time. If you give the sound man a solid signal during your performance (by literally putting the ball of the microphone in your mouth), he has a lot more control over your volume. If he’s good he will ride (keep his finger on the fader) your vocal for your whole performance. If you give him a solid signal he can adjust it from his end. It’s a great strategy if you have a conscientious engineer. If your engineer is a house guy who’s just punching the clock, you’ll need to master the subtlety of the dynamic mic yourself.

It takes practice. Go into your rehearsal space and flip on your PA. Sing normally and adjust the distance between your mouth and the mic until you find the sweet spot. Each voice/microphone combination is slightly different. Once you have your sweet spot, try yelling or singing at a high volume. You may have to back off several feet to avoid distortion. Try whispering. Play around with getting to know the microphone. It will teach you about your rehearsal space setup. When you get in a live setting, do the same thing. As you gain more experience with singing, you will automatically sense the dynamic and adjust.

A dynamic mic isn’t great at picking up subtleties, so use them when the instrument you’re trying to capture isn’t subtle! Dynamic microphones are good on guitar amplifiers close up. Electric guitars and amplifiers are loud and they can go from quiet to loud with one click of a distortion pedal. A dynamic microphone can withstand drastic pressure changes. They are good on snare drums and toms for the same reason. Use a large diaphragm dynamic mic on the inside of a kick drum.

The Condenser Microphone

A condenser microphone, on the other hand, is good at capturing subtleties. They are used for singing in the recording studio. When you’re singing into a condenser you need to use a pop filter. This is a ring covered with a piece of thin nylon fabric that stops the plosive sounds (the letter p mostly) from bottoming out the diaphragm of the microphone. A condenser microphone picks up sounds surrounding the mic. So, if you’re in a big cavernous room, it picks up the reverberations of the room itself (which can be a good thing, unless you also have airplanes flying overhead). This is why singers use a sound proof booth. The booth greatly diminishes surrounding sounds, so you only get the voice. Usually when you cut a vocal in a booth, you will need to add some reverb from a plug-in or a piece of outboard gear because the vocal track is so “dry”.

Use a condenser on acoustic instruments, like guitar, piano, strings, harps, etc. Instruments with a mellow, smooth sound are great when captured with a condenser. Condensers pick up the nuances that give your recording character. Each instrument has it’s own voice. The more good character you capture in a recording, the better your recording will be.

Side note: Condenser microphones require phantom power. This is a little charge of electricity that “powers” the microphone. Most mixing boards are equipped with phantom power. There is usually a little switch on the board you turn on. Without phantom power these microphones will not work.

Break the Rules

These are the rules, and of course, rules are meant to be broken. There is a rumor that Anthony Kiedis sung most of The Red Hot Chili Peppers’ “Blood Sugar Sex Magic” through a dynamic microphone. I don’t know if that’s true, but I do believe some of the parts were sung on a simple dynamic like a Shure SM58. If it sounds good, it sounds good. Most of the time, a dynamic microphone will sound thin and nasally on a studio vocal, but with the right scream, it might just work.

I often use a condenser mic on a guitar cabinet. I won’t push it right up into the speaker cone as I would with a dynamic, but I will give it a foot or two depending on the volume of the guitar part. As long as you don’t send too much volume through the diaphragm, a condenser can sound beautiful on a loud, crunchy amp. Many engineers use a condenser on the outside of a kick drum. In combination with a large diaphragm dynamic on the inside of the drum, it can be exactly what you want to hear (click and woof). As long as you’re careful, you can try a condenser on just about anything. If you’re using a condenser and it sounds too pretty, throw a dynamic in there. Maybe some lo-fi grit is just what your recording needs.

As I said above, this blog isn’t technical, but hopefully it gives you a feel for these two styles of microphones. It’s useful to know the rules and apply them accordingly. But always keep your mind open and use what you have in the studio to get the best and most interesting tones you can.

*The diaphragm on a microphone looks like a small backwards speaker cone. Instead of pushing sound out like a speaker, it receives sound. A condenser microphone’s diaphragm moves more and is more delicate. A dynamic microphone’s diaphragm is stiffer and can take more impact.